Today’s panel is discussing the impact of recent intellectual property disputes on the financial services community. As a Commissioner of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), I have been asked to comment on the role, if any, federal agencies such as the CFTC may play in determining or influencing the outcome of these intellectual property claims among financial service providers. At the heart of this issue is whether federal agencies have the authority and desire to override or amend intellectual property claims, some of which are Constitutionally-based, to promote a broader market principle, such as maximizing competition and innovation. While I will not get into the specifics of any intellectual property cases today, I will try to walk through the guiding principles that this agency should consider in determining its responsibility.

Broadly speaking, the two most significant trends that have impacted the futures industry over the last five years are technology and competition. Today’s discussion on intellectual property is a highly visible example where those two powerful forces intersect.

The passage of the Commodity Futures Modernization Act (CFMA) in 2000 opened up this industry to greater competition. Since 2000, the CFTC has designated eight additional futures exchanges as contract markets, and another 13 exchanges are qualified to operate as exempt markets subject to limited CFTC oversight. Unlike the pre-CFMA years, exchanges, new and old, now aggressively cross-list the products of rival exchanges in an effort to capture market share.

In this competitive environment, the CFTC’s role has shifted as well. The CFMA transformed the CFTC from a frontline agency involved with the daily business decisions of exchanges and firms to an oversight agency ensuring that exchanges and firms have the proper systems in place to protect the markets and the public. With markets now adhering to a risk-based regulatory structure tailored to its participants and products and held in check by the powerful forces of market discipline, other private legal protections, including intellectual property laws, have become increasingly important to markets in defending their interests. Compared with five years ago, exchanges are much more attentive to the possibilities of patenting, trademarking, or copyrighting their intellectual property in order to protect their investment in new trading technology and the licensing potential of their products and inventions.

The protection of intellectual property is imperative to the proper functioning of a market economy and free society. It is such an important right that the Founding Fathers articulated its protections in Article I of the Constitution, stating that Congress shall have the power to “promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.” Because the private ownership of property is such an important tenet of our political and economic system, the presumption should be that individuals be afforded their legal right to protect these interests. The question today is whether there might be an overriding public interest that affects this presumptive right?

On this question, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) in a recent report[1] noted that certain intellectual property claims may work against the public interest. The report states that although the patent system does, for the most part, achieve a proper balance with competition policy, certain questionable, obvious and vague patents may actually impede innovation and competition. With recent increases in patent applications (due in part to a 1998 court ruling that business method patents are protected subject matter) and the expense involved with litigating these property rights, the FTC believes that certain reforms are necessary to ensure that patent protections are properly granted with competition policy in mind.

As an example, the FTC cites the questionable patent of George Seldon, who in 1895 patented the idea of putting a gasoline engine on a chassis to make a car. Although this patent was seen by most as overly broad and vague, the association that bought the license from Mr. Seldon successfully collected hundreds of thousands of dollars in royalties—raising costs and reducing automobile output for many years—before Henry Ford and others challenged the patent in 1911, significantly narrowing its scope.

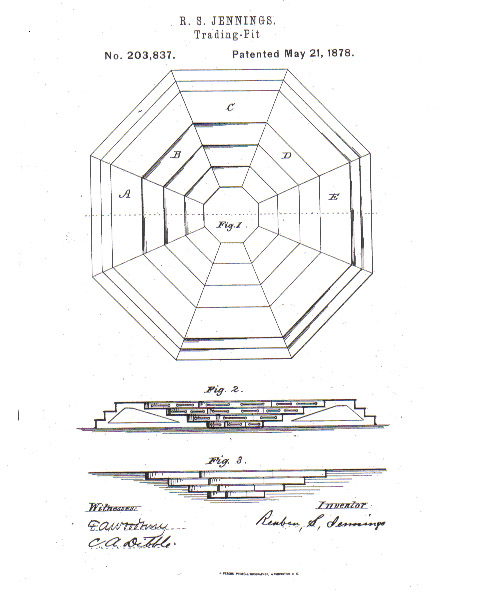

Questionable patents are not new to the futures industry. For example, in 1877 Reuben S. Jennings of Chicago patented his invention of the trading pit. See diagram. The patent states that the pit “furnishes sufficient standing room, where persons may stand and conveniently trade with persons in any other part of the pit or platforms. It has great acoustic advantages over a flat floor.” Immediately after receiving his patent, Jennings served notice to the futures exchanges, demanding a royalty payment from those using the trading pit design. The courts ultimately overturned this patent when challenged.

Are there ways to better ensure that questionable intellectual property claims are not misused to “shake-down” legitimate market participants for payment? One straightforward way for the CFTC and other federal agencies to aid in lessening questionable patents is to offer their expertise to the Patent and Trademark Office (PTO) before patents are issued. The CFTC’s knowledge would be invaluable in determining the scope of prior art when examiners from the PTO look to grant a patent involving the futures industry. Mark Young recently suggested this idea in a recent article in FIA Outlook Magazine and I think it deserves some serious consideration as a means for reducing the questionable patents that are granted in the financial services industry.

In addition, the CFTC may also lend its views in intellectual property disputes by filing amicus briefs involving those claims that involve a mandate provided the CFTC in statute. The Securities and Exchange Commission has already done so in several intellectual property cases. Although this involvement should only be taken in rare circumstances and does not guarantee the court’s consideration of the agency’s comments, the CFTC should not hesitate to voice its views when a private right of action may jeopardize its public mission.

The industry itself should also consider a more proactive approach in the patent application process. It is my understanding that some financial services trade associations have discussed developing a centralized database for prior art that would be utilized in determining the validity of patents. Other associations plan to set up websites and chat rooms to serve as a forum for sharing dialogue and information on intellectual property issues. Because decision-makers in this area have only begun to gain an expertise in the financial services sector, industry associations with specialized expertise could be invaluable to bridge this knowledge gap.

The FTC also recommends several additional steps that might help to achieve a more appropriate balance between patent protections and fair competition. In particular, the FTC suggests that Congress authorize a more robust “post-grant” review process for patents that would enable opposing views to challenge their validity before expensive litigation commences. The FTC also suggests that PTO examiners both consider competitive harm in their cost/benefit analysis before issuing a patent and involve the antitrust agencies in some sort of consultation role. These recommendations would require Congressional action, some of which is already pending in legislation.

The FTC’s suggestions all aim to work within the intellectual property laws to improve the quality of these claims. But can the CFTC use its statutory authority to directly limit the effect of legitimate intellectual property rights when their enforcement harms the broader marketplace? This is a difficult question given the Constitutional basis of some of these intellectual property protections.

There is nothing in the Commodity Exchange Act (CEA) that specifically addresses intellectual property rights. Although the CFTC has exclusive jurisdiction over futures trading, there is a general savings clause in our statute that preserves the effect of other federal statutes, which would likely include patent, trademark and copyright law.

The CEA does provide some broad guidance to our discussion. Based on the interstate commerce clause of the Constitution, Section 3 states that one of the purposes of the Act is to “promote responsible innovation and fair competition among boards of trade, other markets and market participants.” To enforce this goal, Section 15(b) of the Act states that “the Commission shall take into consideration the public interest to be protected by the antitrust laws and endeavor to take the least anticompetitive means of achieving the objectives of the Act when issuing any order or adopting any Commission rule or regulation.” Core principle 18 for designated contract markets also requires exchanges to avoid acting in an anticompetitive manner that results in an unreasonable restraint on trade. To the extent that the CFTC finds that an intellectual property claim materially harms market competition, these provisions could arguably provide the agency with the legal basis to limit the scope of these intellectual property rights.

Although the CFTC can debate whether it has the legal authority to affect certain intellectual property claims when a broader market principle is at stake, it is quite another question to determine under what circumstances the CFTC should exercise such authority. A patent that appears to harm the marketplace in the short term may end up promoting innovation and competition over the long haul. The financial services industry and its regulators have only recently begun to wrestle with these complex issues and the impact of intellectual property applications on this industry is difficult to determine so early in the process.

Indeed, there are examples where intellectual property protections have worked well in our industry, such as the exclusivity of licensing arrangements where exchanges compete for the exclusive right to use an index name or valuation in forming futures products. This has allowed competition between exchanges to exist and flourish without treading on these property rights.

In closing, this agency should proceed with caution before acting to directly limit the use of intellectual property rights by market participants once they are legitimately asserted. Like most in this industry, the CFTC is only beginning to consider how to approach balancing these property interests against the goals set out in the CEA. However, I would suggest that the CFTC, as well as the industry, has a role to play in lending its expertise to the intellectual property agencies and others involved in the process to ensure that questionable claims are not granted or enforced. Other reforms within the patent system itself, as suggested by the FTC, would also go far toward improving the system and ensuring that competitive concerns are taken into account.

[*] The views of the

Commissioner are his own and do not necessarily represent those of the

Commission or its staff.

[1] Federal Trade

Commission Report; To Promote Innovation: The Proper Balance Between

Competition and Patent Law and Policy; October 2003.